Increasing Your Luck Surface Area

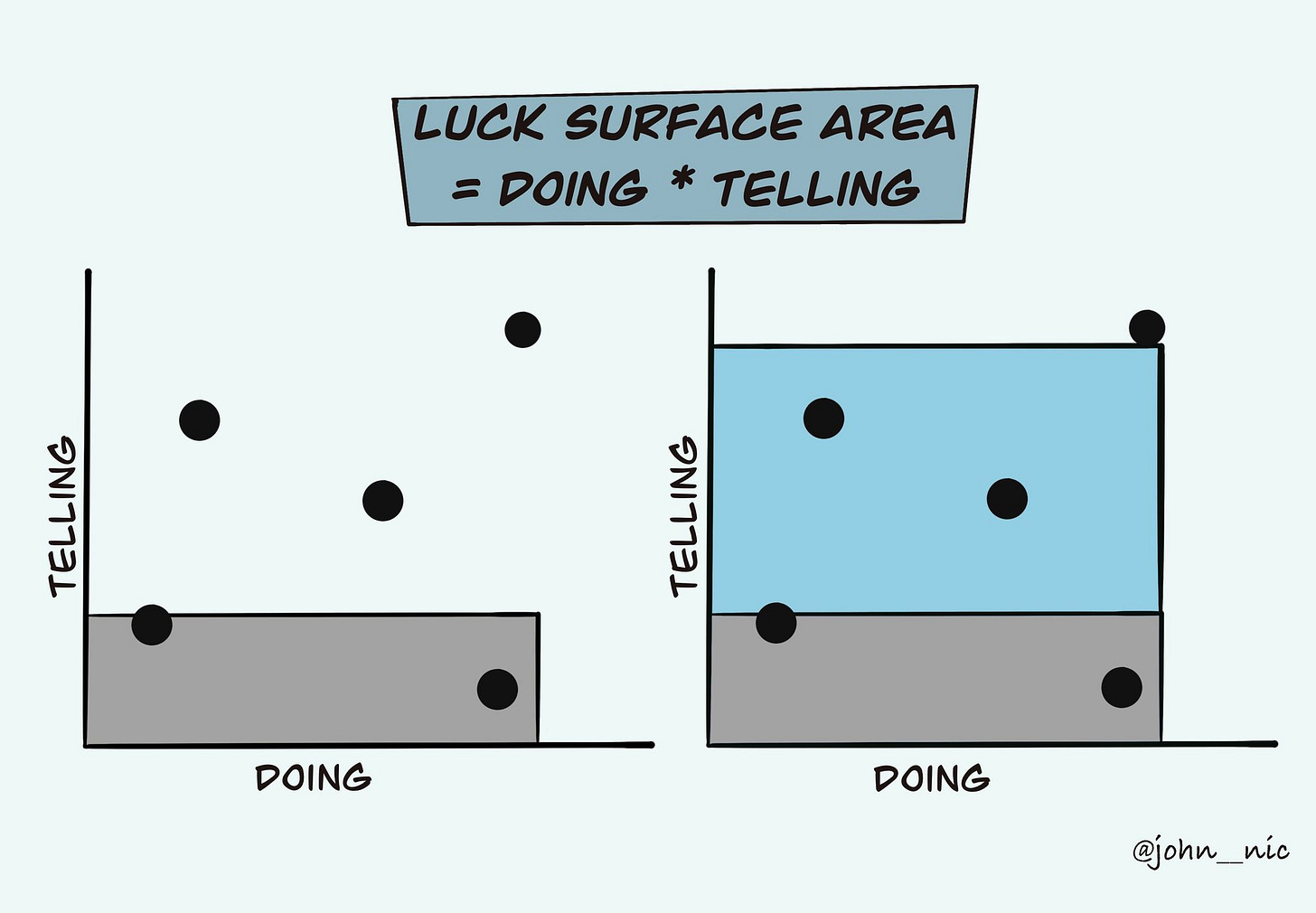

“The amount of luck that you have in life is how much value you create, times how many people you tell about it.” - Patrick McKenzie

Doing great work is only half the job. If you want to increase your chances of success (your luck), you need to tell people about your work as well. This is something I’ve learned the hard way.

Dispelling the schoolboy mindset

School prepared me for life in many ways. I understood the value of hard work. I made friends and learned to socialize (awkwardly at first and a bit better later on). I played sports and picked up hobbies. For all its benefits, school failed me in one big way. I learned how to do the work, but I missed the lesson that I had to promote my work as well.

I fostered what I call the “schoolboy mindset”. You write the exam or complete the assignment and you know the teacher will mark it. You don’t have to write the exam, drive to their house and explain what you wrote. There is an agreement - the teacher or lecturer will review your work and give you a grade. Hard work generally translates into good results. What you put in is what you get out.

This is how I approached my first job. I assumed if I just worked hard and did my best, I would be rewarded for it. I would stay up late at night building insurance tools and products. In my view, some of the best tools our company delivered to brokers and clients. I enjoyed the work. I learned a lot, but I wasn’t good at showing everyone what I had done. I didn’t think it was necessary.

The schoolboy mindset limited me. My colleagues who were better at promoting their work were, funnily enough, also better at getting promotions. While I was doing work for my manager, my colleagues did the work for their managers, but also told their manager’s manager and other teams in the business. I thought they were stooping low to get ahead. But in hindsight, their approach was right. They were focusing on what mattered - showing their work.

The case for showing your work

This sentiment is echoed by writer and software developer Patrick McKenzie (better known as @patio11 on Twitter). Patrick has created multiple software businesses, including a gaming company that teaches programming called Starfighter and a consultancy called Kalezumeus Software. He currently accelerates startups at payments company Stripe.

Patrick experienced the increased serendipity that comes from building in public first-hand. He started writing online in 2006 when blogging was still very new. He had been described as a good writer by his lecturers and he wanted to continue exercising this muscle. He wrote about his work and the software he was building. By sharing his ideas, he experienced some unexpected benefits. He received feedback from others and created hype about the products he was planning to launch. By going one step further and publishing his writing, Patrick created luck for himself.

As he explains in this podcast with David Perell:

“It is too easy to hide your lamp under a bushel, to think that you are just going to do the best work possible and you will naturally be rewarded for that. The world is not set up to reward people just for doing great work.”

“There’s an incentive structure around you, there are decision makers around you who will largely not be apprised of the value you’re creating unless you make it your mission to also apprise them of the value of that.”

Shine a light on your work to help yourself and others.

You need to eat

Like Patrick, I come from a background where self-promotion is discouraged. You don’t toot your own horn. For the most part, I am grateful I was raised this way. Being boastful is a surefire way to alienate people and lose friends. Humility and a sense of gratitude are good principles to foster.

Despite the virtues of modesty and despite how gross self-promotion feels, you need to shine the light on your work sometimes. Not doing any ‘telling’ limits your chances of success. You need to eat, as Patrick says:

“Self-promotion is kind of like self-cooking, if you don’t do it and you don’t pay somebody to do it, and you aren’t in a family with somebody who’s going to do it for you, then you’re gonna go hungry.”

There are better and worse ways of promoting your work. We all know people who employ too much telling and not enough doing - the Dunning-Krugers1 of the world. It’s easy to see through them. They are found out because they can’t fool everyone all the time. Their luck surface areas are small since their ‘doing’ component is negligible.

Find the line between too much modesty and going hungry. Making noise without tact is detrimental, but not making any noise means you won’t get noticed at all.

The same rules apply everywhere

Doing without telling is a missed opportunity. The same principle applies for creators, employees in the workplace, entrepreneurs and startups.

If you are a creator, you need to publish your work. Nobody is going to break into your house to have a party with you. You need to go out to a bar to meet people (or whatever people do nowadays to socialize). In the same way, you need to put your creations out there. Nobody will randomly reach out to you to hear your ideas. You need to build a site and point people there to attract attention.

The same goes for corporate roles. As Louie Bacaj points out, you need to do two things to move up in your career. They might sound familiar.

Add value. Make the pie bigger for everyone. The doing.

Make noise. Point to how you made that pie bigger. The telling.

The formula to get promoted has two key steps.

Step 1: Add Value

Step 2: Make Noise— Louie Bacaj (@LBacaj) December 22, 2021

You need both components to make an impression at work.

Ditto for entrepreneurs and startups. Michael Sklar sums it up as follows:

Please the user. Build a good product. The doing.

Please the salesperson. The distribution and marketing. The telling.

Indie developers, Silicon Valley has graveyards filled with companies that had good products.

Many of those companies failed because product marketing was a blindspot.

Product management = please the user.

Product marketing = please the salesperson/buyer.— Michael Sklar (@michaelsklar) January 13, 2022

The products that are successful rely on distribution. The companies that are successful build a prototype and get it in front of users as quickly as possible.

Ripples

Thinking back to my first role, it is clear that my approach was naive. I was dropping a stone in a pond, while my colleagues that got ahead were skipping pebbles across a big lake. My stone made a splash and sank to the bottom of the pond, while their pebbles made visible ripples across the lake.

It’s important to remember - the work doesn’t always speak for itself. Next time you do good work, write an essay or build a product, don’t forget to tell people about it. Pull your lamp out from under the bushel to maximize your luck surface area.

Thanks to Jess Schanz, Nic Rosslee, Mujidat Oladeinde, Melissa Menke and Arthur Plainview for reading drafts of this essay.

Notes:

The Dunning–Kruger effect is the cognitive bias whereby people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability.

Hit reply below with your thoughts and comments. Feedback keeps me going.