When I was in primary school, I used to be really into swimming. We had training every day (sometimes twice a day) for one and a half hours. I was by no means a great swimmer, but I trained hard and I had high expectations.

Unfortunately I didn't perform well at galas. Kids I consistently beat during training were now beating me on race day. I didn’t understand why this was happening. It made me really upset. Why was my hard work not translating directly into results? Why was I failing when it mattered?

In hindsight there could have been many reasons for this. Perhaps the other swimmers were not giving it their all at training. Or they were less nervous on the day of the race. Or they were simply better at swimming than me.

After a few disappointments at galas, I decided to try a different route. I told my parents I wanted to see a sports psychologist. To help me perform on the day of the race. Quite a bold request from a twelve-year-old, but I was determined. Thankfully they acquiesced and made it happen.

I ended up at a wonderful guy called Clinton Gähwiler at Sports Science in Cape Town. Clinton taught me many things, but two lessons stood out: control the controllables and choose the glasses through which you view a situation.

Control the Controllables

First lesson - focus only on the things that are in your control.

Concentrate on the things you can influence. Leave the rest to play out as fate intended. Don’t allow the uncontrollables to take up any of your headspace or energy, there is no point worrying about them.

Applied to swimming, I could control, among other things, my training, my diet, my sleep before the race and my attitude. I couldn’t control how fast the other guys swam; I just had to focus on the line in the pool below me. I had control over my small sphere of influence. There was no point stressing about the vagaries of the world outside this.

Clinton’s lesson made sense. It allowed me to stop beating myself up when I didn't perform well. As long as I gave my best, and did everything in my control, that was a good outcome. More importantly, while I couldn’t control the result of an event, I realised I could control my reaction to the outcome. No matter the result, in victory or defeat, it was in my power to smile and shake hands and congratulate the other swimmers afterwards.

A great example of this mindset can be found in the 2015 film Bridge of Spies, starring Tom Hanks and Mark Rylance. Set during the Cold War, the film covers the story of American lawyer James B. Donovan (Hanks), who has to negotiate the release of a U.S. Air Force pilot in exchange for Rudolf Abel (Rylance), a convicted Soviet KGB spy.

Throughout the film, Abel doesn’t have many options. First when he is convicted as a spy and later when he is returned to the Soviet Union in the hostage exchange, after which he will face almost certain death. Each time, Donovan would ask him if he’s worried and his answer would inevitably be: “would that help?”

His deadpan response and stoic character in the face of adversity makes you like the character, even though he is a Soviet agent. He remains calm and controls his emotions, which are the only things he can truly influence. He knows he can’t control his fate, so what point is there in worrying about it.

Choose Your Glasses

Second lesson - choose the glasses through which you view a situation.

Your perspective influences your response. You can view the world through dark, grey coloured glasses with everything and everyone against you. Alternatively, you can re-frame your situation and change the lens to a more rosy hue.

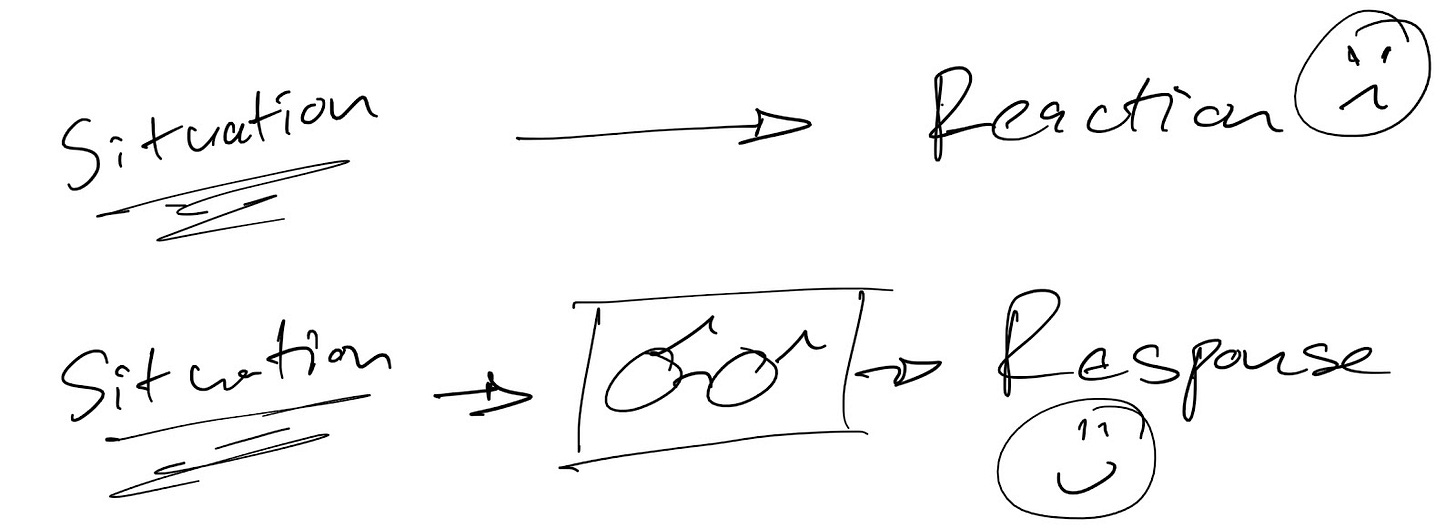

When confronted with any situation, whether good or bad, pause and choose your glasses before deciding on your response. Merely reacting to a situation is often coupled with acting out and feelings of regret afterwards. Pausing and re-framing allows for a more appropriate response.

Bringing it back to swimming. Instead of getting upset when I lost a race, I could view it as an opportunity to learn or a motivation to improve for next time. Instead of lashing out and complaining about the conditions of the pool, I could use a more positive lens and be grateful for the opportunity to compete.

The second lesson always reminds me of "If" by Rudyard Kipling. The whole poem is beautiful, but these lines stand out for me:

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same;

… you’ll be a Man, my son!

In moments of weakness, I strive to be the person Kipling portrays here. Someone who is consistent no matter the outcome. Someone who acts with grace in any situation. Someone who is resilient.

All Together Now

Bringing Clinton’s two lessons together: control what you can and choose your response. Or, stated differently, you can’t control many things, but you can control how you respond to anything. This is truly a superpower.

Viktor Frankl underlines this point in Man’s Search for Meaning. Originally published in 1946 under the German title “trotzdem Ja zum Leben sagen: Ein Psychologe erlebt das Konzentrationslager” or “Nevertheless say yes to life: A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp”.

Frankl asserts that not only can you choose your response or attitude in any situation, it is also the last thing you can hold onto when everything else is taken from you.

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Frankl, a Jewish neurologist and psychiatrist, who often saw patients for free, was thrown into the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1942 under the Nazi regime. After two years he ended up in Auschwitz, the main extermination camp, where only one out of every 28 prisoners survived. He was one of these lucky few, but his father, mother and wife along with countless others perished.

Frankl witnessed that some camp prisoners were able to brave the worst conditions imaginable despite the odds being stacked against them. He realised the prisoners that survived found a way to cling onto their last bit of humanity. Their attitude was something no one could take away.

They had lost their families, their homes, their jobs, even the clothes they carried into the camps, but they could choose their outlook on life. The prisoners always had the freedom of choice, even in severe suffering. They could hold onto hope in the future and find meaning in this. As he remarks:

“To be sure, a human being is a finite thing, and his freedom is restricted. It is not freedom from conditions, but it is freedom to take a stand toward the conditions.”

Ripple

I didn't go on to become a great swimmer. I think I performed slightly better at galas, but not significantly. I also started playing team sports and stopped competing in swimming, using it mainly to stay fit.

The improved results were hardly the biggest takeaway from the experience though. The lessons I learned from Clinton were the true highlights. Lessons I carried with me into the rest of my life.

Apart from the obvious benefits these tools had for me in my studies and in my career, it also had ripple effects on the people close to me. Your mood can influence others. The more resilient you are, the more you can control your attitude, the better this is for your family and loved ones.

To this day, I think about the ‘controllables’ and the ‘glasses’. I can’t control whether the outcome will be triumph or disaster, but I can decide how I will meet with these two impostors.

Thanks to Jess Schanz, Nic Rosslee, Catalina Muñoz, Chris Wong, Melissa Menke and Tommy Lee for reading drafts of this essay and thanks to Clinton Gähwiler for being my sage when I needed him.